|

Background: Intimate partner violence (IPV) is common worldwide and occurs across social, economic,

religious and cultural groups. This makes it an important public health issue for health care providers. In

South Africa, the problem of violence against women is complex and it has social and public health consequences.

The paucity of data on IPV is related to underreporting and a lack of screening of this form of violence in health care settings. Objectives: The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of IPV and explore the risk factors

associated with this type of violence against women who visited a public hospital in Botswana. Method: A descriptive, cross-sectional survey was conducted among randomly sampled adult women aged

21 years and older, during their hospital visits in 2007. Data were obtained by means of structured interviews,

after obtaining written and signed, informed consent from each participant. Results: A total of 320 women participated in this study. Almost half (49.7%) reported having had an

experience of IPV in one form or another at some point in their lifetime, while 68 (21.2%) reported a recent

incident of abuse by their partners in the past year. Experiences of IPV were predominantly reported by women

aged 21 - 30 years (122; 38%). Most of the allegedly abused participants were single (173; 54%) and unemployed

(140; 44%). Significant associations were found between alcohol use by participants' male intimate partners

(X2 = 17.318; p = 0.001) and IPV, as well as cigarette

smoking (X2 = 17.318; p = 0.001) and IPV. Conclusion: The prevalence of alleged IPV in Botswana is relatively high (49.7%), especially among young adult women,

but the prevalence of reported IPV is low (13.2%). It is essential that women are screened regularly in the country's public

and private health care settings for IPV.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is common worldwide and has been recognised as an important public

health problem with immense consequences at both social and political levels.1IPV occurs across all

populations, irrespective of social, economic, religious or cultural groups and the only variation is in the patterns of violence

in different populations.2,3There is little consensus among researchers on exactly how to define the term 'intimate partner violence', and therefore the definition

of the term IPV varies widely from one study to another, making comparisons of the description of the term difficult. IPV is sometimes

referred to as domestic violence. The word 'violence' is also used interchangeably with 'abuse'. In South Africa, the problem of violence against women is complex and has social and public health

consequences.4 This makes it an important public health issue for health care providers.

Most of the time the abuse from IPV is hidden from the public's view and society remains uninformed of the nature and extent

of such violence and abuse. Consequently, this form of violence and the extent of the problem cannot be directly observed. Of concern is the paucity of data on IPV due to 'underreporting' and 'lack of screening', which contributes to the

complexity and the magnitude of this form of violence, especially against women. Furthermore, obtaining reliable data on

IPV is a complicated and intricate task, because of the private and intimate context in which this form of violence and abuse

often takes place and also because of methodological challenges imposed by the nature of such studies.5 Research on violence against women is considered an important objective of any programme designed to eradicate this problem.

At the fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing in 1995, one of the strategic objectives established was to study the

causes and consequences of violence against women and the efficacy of preventive measures, thus encouraging governments and

organisations to promote research in this area.6 A World Health Organization's (WHO's) population-based survey on women's health and domestic violence against women in 2005

established that 10% - 69% of women had been assaulted by their male intimate partners at some stage in their lives, and that

15% - 30% had been assaulted in the previous year.7 The objective of this study was to develop

methodologies to measure

violence against women and its health repercussions in different cultures. Furthermore, the results of the WHO survey showed that the national lifetime prevalence of partner abuse among

South African women was estimated at 13% and occurrence in the previous year at 11%. The Eastern Cape was found

to have the highest lifetime prevalence of 27% and previous-year prevalence of 11%.4 In Africa, men are

seen as the head of the marriage or relationship, which indirectly promotes either verbal or physical abuse towards their

female partners.8The latter has also been observed in Mochudi, a village in Botswana, which shares common socio-cultural

features with other southern African countries.9

Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the Medunsa Research Ethics Committee of the University of

Limpopo (MCREC/PH/114/2007), South Africa. The study was conducted following the standard ethical guidelines

on conducting gender-based violence studies as stipulated by the WHO,10and the

recommendations prescribed

in the ethical and safety guidelines for research on domestic violence.11Written and signed informed consent

was obtained from each participant prior to data collection. Special arrangements were made for participants to be interviewed

after their consultations. Participants were informed of their voluntary participation and that they could decline to participate or

withdraw from the study at any time, without any negative consequences. Confidentiality and anonymity of participants were maintained

throughout the study by non-disclosure of information obtained and analysis of data as 'group' data. Participants who had psychological

distress during the interviews were referred to the hospital social worker for counselling and follow-up care, as pre-arranged by the

researchers.

This study was conducted to determine the prevalence of IPV and explore the risk factors associated with this

type of violence against women who visited a public hospital in Botswana. A descriptive, cross-sectional survey was

conducted among adult female participants aged 21 years and older (the lower age limit was chosen because of consent

rules in Botswana) who sought medical care for themselves or their children in a public hospital in Botswana. Participants

were recruited after their medical history was taken, in order to exclude those with serious physical illnesses

(e.g. uncontrolled blood sugar, major injuries, and unconscious, agitated or depressed patients). Moreover,

participants were interviewed after their consultation, as their medical conditions could then be considered as stable.

A hospital setting was used for this study in order to reduce the risk of further abuse of participants, especially if

accompanied by their abusive intimate partners.12The health setting has been identified as one of the best

contexts in which IPV can be identified and studied, mainly because of its accessibility and because women who have experienced

this form of violence or abuse make greater use of health services than those who have not suffered such an experience.13,14 Two trained, female research assistants fluent in Setswana (participants' home language) and English assisted with data

collection. The statistics program SPSS version 14.0 was used to analyse data and a chi-square test and univariate logistic

regression analysis were used to determine the relationships between socio-demographic characteristics and behavioural

risk factors associated with IPV. Odds ratios were obtained for each risk factor and logistic regression analysis was done

to determine the relationship between the risk factors and IPV.

From a sample of 352 that was recruited, a total of 320 adult women who attended the outpatient department at a public hospital in

Botswana consented to and participated in this study (a 90.9% response rate). Participants were enrolled consecutively over a three-month

period on outpatient days that were quieter - hence some days were omitted. Some participants were recruited and agreed to participate

in the study but because the interviews were conducted after their consultations, they did not come back to the researchers as they

were in a hurry to return home.

|

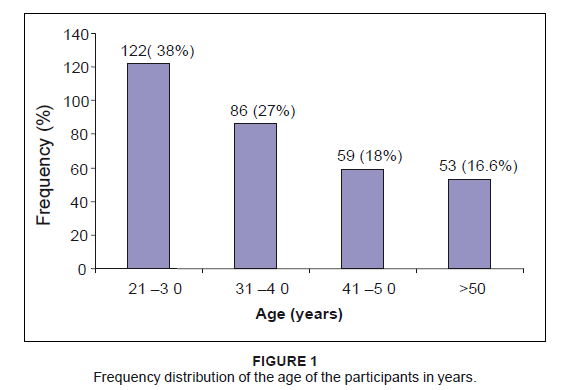

Figure 1: Frequency distribution of the age of the participants in years.

|

|

|

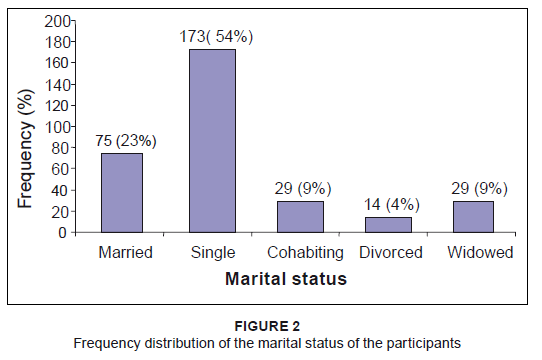

Figure 2: Frequency distribution of the marital status of the participants

|

|

|

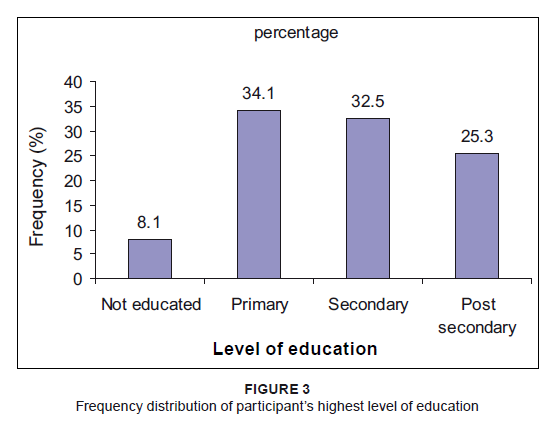

Figure 3: Frequency distribution of participantís highest level of education

|

|

|

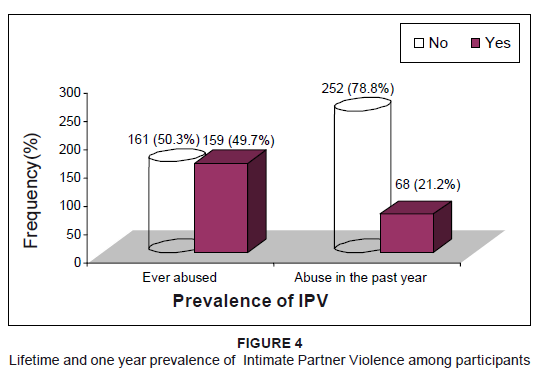

Figure 4: Lifetime and one year prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence among participants

|

|

Socio-demographic characteristics

Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of participants' age groups in years. The age group 21-30 years comprised 122 (38%)

participants and 86 (27%) subjects were in the age group 31-40 years. Results indicated the participants' marital statuses at the time of the study as follows: 173 (54%) were single, 75 (23%)

were married, 14 (4%) were divorced and equal proportions indicated that 29 (9%) were widowed and cohabiting with their

intimate partners (Figure 2). The majority (91.9%) indicated that they had formal education, of which 25% had post-secondary level education. Only 8.1%

indicated that they did not have any formal education (Figure 3).

Participantsí employment status and income

According to the results, 140 (44%) participants were unemployed and had no source of income,

117 (37%) were formally employed either by the government or in private establishments, 27 (8%) were self-employed and 11%

were engaged in casual jobs. Of those employed, 78 (43%) indicated that they earned below BWP1000 per month (approx. USD140; Table 1).

|

Table 1: Employment status and income of participants

|

|

Table 2:The use of alcohol and other drugs by intimate partners

|

Prevalence of IPV

Participants were asked if they had experienced any form of abuse in their relationships with their intimate male

partners (i.e. either their current or previous partners, or spouses). This was categorised into: (1) a lifetime, or

(2) within-one-year experience of IPV. As depicted in Figure 4, almost half of the participants (159; 49.7%) had experienced

IPV in one form in their lifetimes, and 68 (21.2%) had had a recent experience of IPV (i.e. within the previous year).

Financial dependence on intimate partners

Participants were asked if they were financially dependent on their male partners.

Responses indicated that 208 (65%) denied financial dependence, compared to 112 (35%) who admitted to such dependence,

as they otherwise had no source of income, being unemployed.

Substance use by participantsí intimate partners

Slightly more than half of the participants (168; 52.4%) stated that their intimate partners consumed alcohol,

of which 54 (16.9%) were habitual alcohol drinkers (Table 2). About two-thirds of the participants (64.1%)

declared that their intimate partners did not use any other recreational drugs. A third (106; 33%) of the

participants' intimate partners smoked cigarettes and only a small proportion (9; 2.8%) indicated that their

partners smoked dagga (marijuana) and used other illegal drugs.

Other factors associated with IPV

Participants were asked about known risk factors associated with IPV. Table 3 shows that the risk

factors considered included, (1) infidelity, (2) questioning of male partners about girlfriends, (3)

performing activities against the male partner's wish, (4) the influence of alcohol, (5) personality

disorders in male partners, (6) asking the male partner for money when he is financially disadvantaged and (7)

refusing to have sexual intercourse with him. The odds ratios were greater than 1 for all these risk factors (Table 3).

Almost all risk factors except the influence of alcohol and personality disorders in male partners were statistically

significant (p-value < 0.005). Chi-square analysis showed a significant association between participants'

marital status and lifetime experience of abuse (c2 = 23.970; p < 0.001) and experience of

abuse in the previous year (c2 = 14.743; p = 0.005).

Reporting of abuse/help-seeking behaviours

Participants who reported experiences of IPV in their lifetime (159; 49.7%) were asked to indicate the person(s)

they had reported the experiences of abuse to. Slightly more than half of the participants (51%) had reported their

IPV experiences to close relatives and 40 (25.1%) had reported to the police. Eight respondents (5.03%) stated that they

had reported IPV experiences to the nearest hospital and an equal number of participants reported it to other people, mainly

social workers (15; 9.4%) and friends (15; 9.4%). The remaining participants (161; 50.3%) indicated that they did not report their

IPV experiences for various reasons (not explored in this paper).

Socio-demographic characteristics

The results of this study showed that IPV is common in young women and those who are economically dependent on

their male partners. These findings concur with those from other national surveys done globally, which show that

IPV is more common among women than men.1,7 A WHO report on violence and health indicates

that young women and those below the poverty line are disproportionately affected by IPV.11 Previous reports on

IPV have shown that the young ages of male perpetrators and their victims could also be a risk factor to violence and abuse

because of various factors such as immaturity, poverty and unemployment.

Prevalence of IPV

The results of this study estimate the lifetime and past-year prevalence of IPV to be 49.7% and 21.2%, respectively.

This indicates a high prevalence of IPV among the study population, that is, one in every two and one in every five

adult female patients who visited the out-patient department of the institution had experienced lifetime and past-year IPV,

respectively. These findings are similar to those from a study conducted in China in 2005, which showed the lifetime and past-year

prevalence estimations to be 43% and 26%, respectively.15In a similar study conducted in Uganda in 2003, the authors

estimated the lifetime prevalence of partner abuse among women to be 54%, while the past-year prevalence was 14%.16 In South Africa, the results of a WHO population-based survey carried out in 1998 estimated the national lifetime prevalence

of IPV among women to be 13% and the past-year prevalence of IPV to be 11%. Furthermore, provincial figures established that the

Eastern Cape province had the highest lifetime prevalence of 27% and a past-year prevalence of 11%.17 Findings from

a similar study conducted among female patients in a public hospital in Durban (KwaZulu-Natal province) showed an estimated

lifetime prevalence of IPV of 38%.18 Data from health care-based IPV prevalence studies in the United Kingdom

in 2004 estimated lifetime and past-year prevalence to be 12% - 46% and 6% - 28% respectively,19 while in the

United States of America in 2002, it was 30% - 39% and 6% - 23%, respectively.20 Although IPV is regarded as a

global concern, the challenge of its underreporting affects the prevalence estimates and magnitude of this form

of abuse.2,19 In 1999, a national study on violence against women conducted in Botswana by the Women's Affairs Department found that

violence against women was an immense problem, with three out of every five women having been a victim of such violence.19

In a similar study in Uganda, the authors estimated the lifetime prevalence of partner abuse among women to be 54%, while

the past-year prevalence was 14%.16A London-based study in 2002 on domestic violence revealed that the lifetime

prevalence of partner violence in health care settings was 41% and the past-year prevalence was 17%.20

Other risk factors relating to IPV

Several risk factors have been ascribed to IPV, including socio-demographic, cultural and behavioural factors.

In this study, as reported by the participants, infidelity and actions against the wishes of the male partners were the

most common risk factors for IPV, with odds ratios of 23.26 (95% CI: 9.31-58.09) and 63.81 (95% CI: 7.10-573.42), respectively.

Other factors with statistically significant p-values included the participants' questioning of male partners about their

extra-marital relationship(s) (p < 0.0001), financial dependence on the male partner (p = 0.002), and refusing

to engage in a sexual relationship (p < 0.0001). All were found to increasingly expose participants to IPV. Regarding alcohol and other substances used by male partners, although there was a significant association

with IPV (c2= 40.967; p < 0.001) it was not reported by most of the participants

as contributing to their experience of IPV. The most common behavioural risk factors associated with IPV found

in studies carried out in China, USA, UK, South Africa, Uganda and Malawi are (1) extramarital affairs, (2) use

of alcohol and other drugs, (3) doing things against the wishes of the male partner and (4) arguments about monetary

issues (especially when the male partner is financially

disadvantaged).2,4,16,

19,21 Results from other studies

revealed that alcohol did not initiate IPV, but worsened its outcomes in terms of severity.19,22

Association between socio-demographic variables of participants and IPV

Several studies have revealed an association between socio-demographic characteristics of both the victims of IPV and the

offenders and significant

relationships.1,3,14,15 The following

factors have been identified as factors that

increase the risk of women to IPV, (1) a relatively young age, (2) poverty or unemployment, (3) being divorced or separated

and (4) a low level of

education.1,2,7,14 The results of this study further showed a strong relationship between the ages of participants and the occurrence of abuse.

This association was only significant (c2= 7.991; p = 0.035) for a lifetime experience of abuse,

where the chances of abuse decreased with increasing age of participants. Such findings (that IPV occurs more frequently in

younger people) was also supported by findings from a study conducted in London in 2002, UK, which confirmed that women younger

than 45 years (with the highest risk occurring between the ages of 16 and24 years) have a higher risk of experiencing IPV than

those older than 45 years.20This has been ascribed to immaturity and lack of patience among partners in a

relationship.1> Results of this study did not reveal any statistically significant

association between age and a past

year's experience of abuse (c2= 4.131; p = 0.248), which is similar to

results of a similar study

carried out in China.15 The reason for this difference is not clear. This study found a strong association (c2= 23.970; p < 0.001) between marital status and

lifetime experience of abuse, with the highest occurrence among divorced participants (93%), followed by cohabiting

partners (75%), singles (49%) and married partners(40%) and the lowest occurrence among widowed participants (34%).

This trend was also found with a past-year experience of abuse. A similar trend and order of occurrence, was found in the

National Violence Against Women Survey carried out in the USA in 2000.2 Several other studies conducted in Botswana,

South Africa, USA, China and Malawi also reported similar associations, with the highest occurrence among unmarried and

cohabiting couples.9,15,17,22 Studies conducted in 2005 in South Africa and Malawi have found that a lower educational status exposes women

to IPV.17,21

The results of this study did not find any significant association (c2= 4.586; p = 0.205)

between the educational level of participants and the occurrence of abuse: both educated and uneducated women experienced

abuse equally. This was supported by the findings of a Ugandan study, which established that the educational level of women

only reduced the frequency of IPV but did not prevent it.16> Unemployment, poverty and economic dependence of women expose

them to IPV.1,2,7This study found that about 44%

of all participants were unemployed and therefore did not earn any income, 35% depended economically on their male partners,

while others depended on parents and relatives. A significant relationship (c2 = 14.890; p = 0.005)

was found between the 'economic status' of abused participants and the experience of abuse and the risk decreased as the amount

of income that was earned increased. This is in agreement with studies carried out in Africa, Asia and America, which found that

women with low socio-economic status are more prone to

abuse.2,7,16,

19,22 A systematic review of relevant studies conducted in the USA, UK and Malawi found that the low educational levels of women

predispose them to abuse by their intimate partners.2,19,21 A similar trend was found by researchers in a

South Africa national survey on partner violence.18 A high level of education, however, does not rule out

violence: it sometimes predisposes women to abuse, especially if the male partner is

less educated.1,7,14 The consumption of alcohol, a major cause of many social vices, has been found to be related to IPV. A number of

studies reveal that alcohol only contributes to violence rather than causing it, and that those women who live with

heavy drinkers are at far greater risk of physical partner violence, which tends to be more serious, than that found

in those not consuming alcohol.19,22 The results of this study also indicated a very strong association

between the frequency of use of alcohol and other drugs (both with p < 0.001) by the male partner and the

occurrence of IPV in their relationships. There are significant differences between studies in terms of the methods used

to measure the presence or absence of alcohol and in the definition of alcohol consumption as a risk factor for the development

of violent behaviour. A Chinese study revealed that the use of cigarettes and other drugs increased the chances of a man to abuse

his female partner.15 This is consistent with the significant association between

the use of other drugs (mainly cigarettes)

and occurrence of abuse found in this study.

Economic dependence on male partner and occurrence of abuse

As indicated earlier, studies conducted in the USA, China, Malawi and South Africa found that economic independence of

women protected them from various forms of abuse by their

male partners.15,17,19,21 The results of this

study are not consistent with these findings, since no statistically significant association was found between participants'

experiences of abuse and economic dependence or independence on their male partners (c2 = 0.447; p = 0.504).

The majority of the women who participated in this study stated that they were not economically dependent on their male partners but,

despite such confirmation of financial independence, about half of them still experienced abuse and the overall prevalence of

abuse was high. Findings from a study conducted in Botswana reported that almost half of the households in Botswana are headed by

women who sustain their families, including their male partners or husbands.9 Our results indicated that the majority of

the participants were unemployed and earned no income. It did not include consideration of others upon whom the women could depend

for financial support.

Study limitations

This study was limited to one public health institution and, although a high response rate was achieved,

the views of other women from other institutions, or in the community, regarding their experiences of IPV,

could not be explored. Furthermore, because this study was self-reported and retrospective, the risk of 'recall'

bias from participants cannot be overruled. In this study participants were recruited in a health care setting,

which increases the chance of a 'selection' bias, as it is known that women who experienced violence and abuse make

greater use of health services, resulting in a possible overestimation of the prevalence of IPV in the general population.

On the other hand, because of the methodological limitations imposed by the nature of this study, the researchers had to protect

participants from further harm and abuse by their partners, as recommended in the ethical and safety guidelines for research on

domestic violence.13 For this reason, participants who were accompanied by their

partners were not included in the

study and thus valuable data could have been overlooked.

|

Table 3: Comparison of cure rates for smear positive pulmonary TB patients among

different directly observed treatment types

|

|

Table 4: Summary of the reasons for choosing different directly observed treatment types

|

IPV is a common public health problem globally. The prevalence of alleged IPV in Botswana is relatively high (49.7%),

especially among young adult women, but the prevalence of reported IPV is low (13.2%). It is essential that women are

regularly screened in public and private health care settings for undisclosed IPV. In order to quantify the magnitude of

such violence, and to implement interventions that can lead to improved outcomes for women who have experienced IPV, it

is crucial that clinical guidelines be made available to enable health care professionals to conduct effective screening

for IPV. It is our view that the risk of benefit versus harm could be determined once the magnitude of IPV has been established

through IPV screening.

1. Heise L, Garcia-Moreno C. Violence by intimate partners. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on

violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization [homepage on the Internet]. 2002 [cited 2009 July13]; 89-113. Available

from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/wrhv1/en/

2. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature and consequences of intimate partners' violence: Findings from the National Violence

Against Women Survey. US Department of Justice [homepage on the Internet]. 2000 [cited 2009 August 30].

Available from: http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/1816pdf 3. Guys ANI, Ushie AP. Patterns of domestic violence among pregnant women in Jos, Nigeria. SA Fam Pract 2009; 51(4):343-345. 4. Marais A, De Villiers PJT, Moller AT, Stein D.J. Domestic violence in patients visiting general practitioners:

Prevalence, phenomenology, and association with psychopathology. SAMJ 1999;89(6):635-639. 5. Ruiz-Perez I, Plazaola-Castano J, Vives-Cases C. 2007. Methodological issues in the study of violence against

women. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:ii26-ii31. 6. United Nations Development Programme. Action for equality, development and peace. Fourth World Conference on Women;

September 1995; Beijing, China [homepage on the Internet]. 1995 [cited 2009 Nov 19].

Available from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/fwcwn.html 7. World Health Organization. Multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women

[homepage on the Internet] 2005 [cited 2009 November 14]. Available

from: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/en/index.html 8. Ilika AL, Okonkwo PI, Adogu P. Intimate partner violence among women of childbearing age in a primary health care centre in Nigeria.

Afr J Reprod Health 2002;6(3):53-58. 9. Women's Affairs Department. Report on the study on the socio-economic implications of violence against women in

Botswana, Gaborone. Botswana: Government Printers;1999. 10. World Health Organization (WHO). Putting women's safety first, ethical and safety recommendations for research on

domestic violence against women. Geneva: WHO; 1999. 11. Ruiz-Perez I, Plazaola-Castano J. Intimate partner violence and mental health consequences in women attending

family practice in Spain. Psychosom Med 2005;67:791-797. 12. Bradley F, Smith M, Long, J, O'Dowd T. Reported frequency of domestic violence: Cross sectional survey of women

attending general practice. BMJ 2002;324(7332):271. 13. Ellsberg M, Heise L. Researching violence against women: A practical guide for researchers and activists.

Washington DC: World Health Organization, PATH; 2005. 14. Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence: A global public health problem. In: World report on violence and health.

Geneva: WHO, 2002. p. 1-21. 15. Xu X, Zhu F, O'Campo P, Koenig MA, Mock V, Campbell J. Prevalence of and risk factors for intimate partner violence in China.

AJPH 2005;95(1):78-84. 16. Wagman J. 2003. Domestic violence in Rakai community, Uganda. World Health Publication (WHP) Review, Winter 2003. p. 7-8. 17. Vetten L. Addressing domestic violence in South Africa: Reflections on strategy and practice. Centre

for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, South Africa. 2005 [cited 2009 Sept 14]. Available

from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/vaw-gp2005/docs/experts/vetten.vaw.pdf 18. Mbokota M, Moodley J. Domestic abuse - an antenatal survey at King Edward VIII Hospital Durban. SAMJ 2003; 93(6):455-457. 19. Finney A. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: Key findings from the research.

2004 [cited 2009 June 09]. Available from: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs04/r216.pdf 20. Richardson J. Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Chung WS, Moorey S, Feder, G. 2002.

Identifying domestic violence: Cross sectional study in primary care. BMJ 2002; 324:274-277. 21. Pelser E, Gondwe L, Mayamba C, Mhango T, Phiri W, Burton P. Intimate partner violence:

Results from a national gender-based violence study in Malawi. 2005 [Cited 2010 March 04]

Available from: http//www.isssafrica.org/pubs/book/intimate partner violenceDec.05 /Ipv.pdf 22. Caetano R, Schafer J, Cunradi CB. Alcohol-related and intimate partner violence among white,

black and Hispanic couples in the United States. J Subst Abuse [serial online]. 2000 [cited 2010 Jan 09];

11(2):123-138. Available from: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh25-1/58-65.htm

|