|

Background: Outcomes of antiretroviral treatment have been documented in both developed and developing countries. It has been reported consistently that the treatment is associated with many adverse events. However, little is known about their impact on the quality of life, clinical management, and survival in children aged less than 6 years in Uganda. Objectives: The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of the adverse events of antiretroviral treatment, their impact on mortality and the change in regimens prescribed to children treated at Mildway Centre in Uganda. Method: A retrospective chart review was performed for children younger than 6 years, treated since the Mildway Centre was opened in 1999. In order to achieve a larger sample, the records of children treated from January 2000 to July 2005 were included in the study. A pre-tested data collection form was used to collate socio-demographic and clinical data of the patients. These included the documented adverse events, causes of death, stage of infection, duration of treatment, regimen prescribed, year of enrolment into the treatment program, as well as whether or not they were still alive. Descriptive statistics were used in the analysis of data. Results: Of the 179 children, the majority were males and had a median age of 4 years. The majority (58.8%) of children had suffered from severe immune depression since they met the WHO clinical stage III and IV, 73.8% had a baseline CD4T of less than 15%. Four regimens were prescribed to the children. The most common was a regimen containing zidovudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine (34.6%), followed by a regimen containing stavudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine (27.9%). Eleven children (6.1%) had their regimen changed, of which six (54.5%) were due to adverse events. The prevalence of adverse events was 8%; of the 14 documented adverse events, the most common were severe anaemia (3), vomiting (3), and skin rashes (3). After 12 months on treatment, 8% of the patients had died. The most common causes of death were infectious diseases (28.6%), severe anaemia (21.4%), and severe dehydration (21.4%). Conclusion: The prevalence of adverse events was 8%; they were responsible for 54.5% of regimen changes and 21.4% of deaths in children treated at the study site. These findings suggest the need for incorporating pharmacovigilance practices into the provision of antiretroviral treatment.

Outcomes of antiretroviral treatment have been documented in both developed and developing countries. It has

been reported consistently that the treatment is associated with many adverse events including gastro-intestinal

disturbances, peripheral neuropathy and others.1,2,3 These adverse events impact not only the quality of

life of the patients but also their clinical management and survial.4,5 However, little is known about

these processes in children aged less than 6 years treated at the study site. Therefore, the purpose of this study

was to determine the prevalence of the adverse events of antiretroviral treatment and their impact on the mortality

and change in regimens prescribed to children treated at Mildway Centre in Uganda.

A retrospective chart review was performed for children aged less than six years treated since the centre opened in 1999. In

order to achieve a larger sample, the records of children treated from January 2000 to July 2005 were included in the study.

Age at the time of enrolment was used for inclusion in the study. Besides age, the other inclusion criteria were that the

children should have been on treatment for at least 12 months, with the treatment having been initiated at Mildway Centre.

Based on the treatment registers, 202 children had been treated during this period. Of these, 16 records could not be

retrieved, while seven records did not meet one of the inclusion criteria in that these children had not completed at

least 12 months on antiretroviral treatment. Hence, 179 records were included in the final analysis. A pre-tested data

collection form was used to collate the socio-demographic and clinical data of the patients. These included the

documented adverse events, causes of death, stage of infection, duration of treatment, regimen prescribed, year

of enrolment into the treatment program, as well as whether or not they were still alive. Descriptive statistics

were calculated but no statistical testing was conducted. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software

(version 17.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Medunsa Campus Research

and Ethics Committee of the University of Limpopo; while the permission to access the patients’ records was requested

and obtained from the management of Mildway Centre.

As shown in Table 1, of the 179 children, 53.1% were 4–5 years old. Their median age was four years, or 48 months.

Their age ranged from 4 to 71 months. About 57% of the children enrolled for treatment were males. The majority (58.8%)

of children had suffered from severe immune depression since they met the WHO clinical stage III and IV; 73.8% had a

baseline CD4T of less than 15%. All children had been prescribed cotrimoxazole as a prophylaxis for opportunistic

infections. Four regimens were prescribed to the children; the most common was a regimen containing zidovudine,

lamivudine and nevirapine. The enrolment into the antiretroviral treatment program for children started in 2000, though

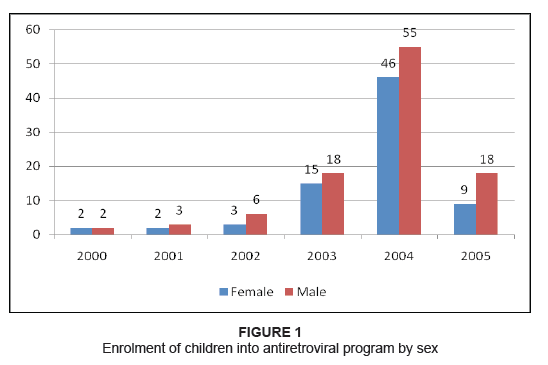

the majority of patients were enrolled in 2004 (Figure 1). The mean duration of treatment was 13.4 months, only 7.3% of

children had been on treatment for more than a year.

|

Table 1: Characteristics of children included in the study

|

|

Figure 1: Enrolment of children into antiretroviral program by sex

|

|

Eleven children (6.1%) had their regimen changed. The majority of regimen changes occurred during the first six months

of treatment. The reasons for changing the regimen were due to adverse events in six cases (54.5%), occurrence of opportunistic

infections such as tuberculosis and pneumonia (18.2%), poor adherence (18.2%) and in one case (9.1%) the reason was not recorded.

The adverse events involved in regimen changes were severe anaemia (three cases), skin rashes (two cases), and peripheral

neuropathy (one case).

|

Table 2: Types of adverse events and impacts in children

|

The prevalence of adverse events was 8%. The most common were anaemia, vomiting and skin rashes. Other adverse events

included diarrhoea, immune reconstruction syndrome, jaundice and peripheral neuropathy. These adverse events impacted

substantially on the children’s treatment; in six children the regimen had to be changed, while in two other

children the treatment had to be stopped (Table 2). At the end of the first year on antiretroviral treatment, the mortality rate was 8%. Three deaths occurred within

the first month, while six others followed within two to six months of treatment. Of the 14 children who died, the

most common causes of death were: infectious diseases (28.6%) such as chicken pox, malaria, pneumonia, and tuberculosis,

adverse events such as severe anaemia (21.4%), and severe dehydration (21.4%). One death (7.1%) was due to severe malnutrition,

while the cause of death was not specified in three cases (21.4%). The characteristics of those who died were as follows: all

but one was younger than 2 years old, 10 were female, and 11 had a baseline CD4T of less than 15%, an indication of severe

immunosuppression. Moreover, while one of the four children enrolled in 2000 died (25%), no child enrolled in 2001, 2002,

and 2003, had died. Most of the deaths occurred in children enrolled in 2004 and 2005, nine out of 101 (9%), and four out of

27 (15%), respectively (Figure 2).

Access to antiretroviral treatment by children is limited in Uganda. Although the Mildway Centre has been operational since

1999, it was the advent of international programs such as the President’s Plan for AIDS Relief and the Global Fund for

HIV, Malaria and Tuberculosis that facilitated the increase in the scale-up of antiretroviral treatment for Ugandan children.

This explains why the number of children on antiretroviral treatment increased substantially from 2004 onwards. However, it is

still unclear why more male than female children were enrolled (Figure 1). With regard to the prevalence of adverse events, it was 8%. This figure is well within the range of between 2.5% – 29%

as reported in the literature.7,8,9 This finding clearly demonstrates a good tolerance of antiretroviral

treatment in this group of children. This has been reported in other settings.

1,3,6,9,10 In this study,

the range of adverse events documented was limited. In fact, only seven adverse events were documented within the first 6 months

of treatment among 14 patients. The most common were anaemia, vomiting and skin rashes. Apart from anaemia, for which some indication

of severity was indicated, there was no such information on other adverse events. The profile of adverse events is consistent with previous studies at the same facility, and reports from studies about antiretroviral

treatment in children in other African countries.11,12,13 Moreover, in contrast to other studies, this study has established

that adverse events were responsible for over half of regimen changes effected among the sample, as well as the institution of a drug holiday

for two children and the cessation of the treatment in three other cases. This substantial impact suggests that children on antiretroviral

treatment should be monitored using pharmacovigilance skills and tools. During the period covered by this study, Uganda did not have any

national pharmacovigilance centre and to date none exists. There is a need for such a centre. With regard to regimens changed, it is noteworthy that all four consisted of two nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (lamivudine

with either, zidovudine or stavudine) plus one non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase efavirenz or nevirapine). The second-line drugs such

as didanosine and abacavir, and protease inhibitors such as lopinavir-ritonavir or nelfinavir were not prescribed even though some children

were supposedly on rifampicin as they suffered from tuberculosis. The regimen change of 6.1% reported here is somewhat lower as compared to

reports by other investigators.4,14 With regard to mortality, the rate of 8% reported in this study is consistent with previous findings in children in other settings in Africa.

However, on a yearly basis, the mortality rate varied from 0% – 25%. In a multi-centre study involving nine countries, Carter et al

.15 reported a mortality of 9%. These findings concur with a well-demonstrated fact that antiretroviral treatment does

save lives, particularly in children because without it, it is estimated that 80% of HIV-Infected children would die before their fifth

birthday.16 Of the 14 deaths reported in this study, infectious diseases were the most common cause of death followed by severe dehydration, and

adverse events. The adverse event associated with death was severe anaemia – a typical side effect for regimens containing

zidovudine. This finding emphasises again the need for close monitoring involving both clinical and biological parameters so that

appropriate interventions could be implemented without unnecessary delays. In this study, over half of the deaths occurred within

the first six months of treatment; 11 of 14 deaths occurred in children who had a CD4T of less than 15%. This suggests that these

children were brought for treatment when their immune systems were already severely compromised. This finding concurs with the view

that the late initiation of antiretroviral treatment is associated with poor outcomes.

12,13,17,18 In order to

improve treatment outcomes, healthcare providers of antiretroviral therapy to children must be aware of the causes of mortality and

the complications of antiretroviral treatment so that they can act swiftly to increase the chance of survival for these children.

Interventions, such as ensuring adherence to antiretroviral treatment guidelines, adherence to prescribed treatment by patients, as

well as the identification of adverse events and treating them appropriately will contribute to effective care. In order to

implement the last intervention, a national drive at policy-making level is required to instil the concept and practice of

pharmacovigilance in clinical practice. Finally, given the design of this study, causal relationships could not be established, nor the reasons for the disproportionate

enrolment of male children and the deaths of female patients. Other limitations include the possibility that some adverse events

may have not been recorded or have been misinterpreted by the healthcare providers.

The prevalence of adverse events was 8%, which was responsible for 54.5% of regimen change, and 21.4% deaths

in children treated at the study site. These findings suggest the need for incorporating pharmacovigilant

practice into the provision of antiretroviral treatment.

1. Bracher L, Valerius N, Rosenfeldt V, Herlin T, Fisker N, Nielsen H, et al. Long-term effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in perinatally HIV-infected children in Denmark. Scand J Infect Dis 2007; 39:799–804. 2. De Baets AJ, Bulterys M, Abrams EJ, Kankassa C, Pazvakavambwa IE. Care and treatment of HIV-infected children in Africa: Issues and challenges at the district hospital level. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(2):163–173. 3. Nabukeera-Barungi N, Kalyesubula I, Kekitiinwa A, Byakika-Tusiime J, Musoke P. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in children attending Mulago Hospital, Kampala. Ann Trop Paediatr 2007;27:123–131. 4. Ble C, Floridia M, Muhale C, et al. Efficacy of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected, institutionalized orphaned children in Tanzania. Acta Paediatr 2007; 96:1090–1094. 5. Bong CN, Yu JK, Chiang HC, Huang WL, Hsieh TC, Schouten EJ, et al. Risk factors for early mortality in children on adult fixed-dose combination antiretroviral treatment in a central hospital in Malawi. AIDS 2007;21:1805–1810. 6. Fassinou P, Elenga N, Rouet F, Laguide R, Kouakoussui KA, Timite M, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapies among HIV-1 infected children in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. AIDS 2004;18:1905–1913. 7. Marazzi MC, Germano P, Liotta G, Buonomo E, Guidotti G, Palombi L. Pediatric highly active antiretroviral therapy in Mozambique: An integrated model of care. Minerva Pediatr 2006;58:483–490. 8. Eley B. Addressing the paediatric HIV epidemic: A perspective from the Western Cape Region of South Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:19–22. 9. Doerholt K, Duong T, Tookey P, Butler K, Lyall H, Sharland M, et al. Outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected infants in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in the era of effective antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:420–426. 10. Barry G, Coovadia A, Marais B, Malan E, Moultrie H. Analysis of HIV-infected infants under 1 year starting antiretroviral treatment at the coronation paediatric HIV clinic in Coronationville, Johannesburg. Proceedings of the XVI International AIDS Conference [abstract MOPE0233];2006 Aug 13–18; Toronto, Canada. 11. O’Brien DP, Sauvageot D, Olson D, et al. Treatment outcomes stratified by baseline immunological status among young children receiving nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1245–1248. 12. Musoke MN, Morelli E, Atai B, Michelin E, Lain MG, Marinello S, et al. Efficacy of HAART in Ugandan HIV-infected children. Proceedings of the XVI International Aids Conference [abstract MOPE026]; 2006 Aug 13–18; Toronto, Canada. 13. Finkbeiner T, Luyirika E, Nabiddo L, Shinde S, Kilule E, Kasule K, et al. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected children in Uganda, 2004–2005 [abstract WEPE0111]. Proceedings of the XVI International AIDS Conference; 2006 Aug 13–18; Toronto, Canada. 14. Wamalwa DC, Farquhar C, Obimbo EM, Selig S, Mbori-Ngacha DA, Richardson BA, et al. Early response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected Kenyan children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:311–317. 15. Carter S, Katyal M, Austin J, Abrams E. Age and CD4 percentage at ART initiation: Relationship to CD4 response over time among children enrolled in MTCT-plus initiative sites [abstract 730]. Proceedings of the 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2007 Feb 25–28; Los Angeles, USA. 16. Penda I. [Therapeutic strategies for children with HIV infectious risks and infected in a country with limited medical resources]. Les defis de la prise en charge des enfants exposes ou infectes par le VIH dans les pays a resources limitees. J Antibiotiques [serial online]. 2009 [cited 2009 Mar 27]; 11(3):158–163. French. [doi:10.1016/j.antib.2009.02.002]. Available from: http://www.em.consulte.com/article/224551 17. Obimbo EM, Mbori-Ngacha DA, Ochieng JO, Richardson BA, Otieno PA, Bosire R, et al. Predictors of early mortality in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected African children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:536–543. 18. Reddi A, Leeper SC, Grobler AC, Geddes R, France KH, Dorse GL, et al. Preliminary outcomes of a paediatric highly active antiretroviral therapy cohort from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:13.

|